Cooperative Entrepreneurship and Slicing Pie

Several years ago, a business owner who attended one of the VEOC’s workshops asked if I’d ever encountered the Slicing Pie framework for managing sweat equity in start-up businesses. I’d not, but was intrigued by his description and ordered the introductory book. What I found was a system that was clearly designed for conventional start-ups but, with some adaptation, could potentially serve as a useful tool for launching worker cooperatives.

For many years, folks who study cooperatives have identified the “Cooperative Entrepreneurship Problem.” In a traditional startup, founders have essentially unlimited upside, so their contribution of sweat equity serves as a gamble, with their time and labor as table stakes with an uncertain future value. It could be worth nothing if the start-up fails, or it could result in a fortune if the company is successful enough to be sold or go public.

Because co-ops are designed for perpetual broad-based ownership, they offer a relatively low barrier to entry for ownership on an ongoing basis. As a result, co-op founder compensation for sweat equity is often either non-existent (uncompensated labor of love) or arbitrary (paying $x per hour for time contributed in the early phase when full cash wages were financially unfeasible). Once a co-op has bootstrapped to a sustainable level, it can deal fairly with compensation going forward, but this can often leave founders with a vague sense of unfairness in relation to members who joined later.

One solution to the “Cooperative Entrepreneurship Problem” is to eliminate the need for sweat equity entirely via sufficient early capitalization. This can be seen at play in locales with highly developed institutionalized co-op capital and support resources like Mondragon and the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy. In those contexts, business development work can be done under the umbrella of existing institutions, and new firms can be launched without the sort of personal risk that individualistic entrepreneurship entails. While this strategy is powerful where it exists, and points to the importance of strengthening co-op development ecosystems everywhere, the reality in most places is that launching a new co-op often requires founder sweat equity.

The Slicing Pie model makes the case that, for companies that utilize sweat equity as part of their launch, participants should agree from the start how to value a wide variety of contributions, from labor to intellectual property to infusions of cash. Mutually agreeing to relative value from the jump is important for heading off future conflicts over how to retrospectively determine the value of different contributions.

While a dollar number is attached to each contribution, those dollars are not a guarantee of that exact amount at a future date, but exist relative to all other contributions. As a result, the size of each contributor’s “slice” of the company’s ownership “pie” is dynamic, changing as they invest their talents, etc., into the enterprise. When the company reaches the point where it can fully compensate folks with cash, it “bakes the pie”, fixing the founders’ relative shares of ownership going forward, with the final value of those stakes being determined by a liquidity event.

The above logic can’t be directly applied to a company formed as a worker co-op from the start, since co-op ownership is intentionally designed to not function as a pie. Rather, owners’ claims are only to a share of profit on the basis of labor contribution, and the residual value of the firm itself can roughly be understood to be a commons. However, the Slicing Pie model does offer an interesting potential entrepreneurial path that combines some start-up and cooperative conversion dynamics.

Essentially, a Slicing Pie co-op start-up would begin looking like a fairly conventional company using the system, with the addition of democratic one-member, one-vote governance. However, the founders would agree from the start not only to the relative value of their sweat equity contributions but also to the terms and trigger conditions for the company’s transition to a co-op upon “Baking the Pie.” Trigger conditions might include such factors as profitability, revenue, number of employees of a defined tenure, etc.

That moment would also serve as the “liquidity event” in the conventional Slicing Pie framework, with an arm’s-length valuation of the company done to determine the fair market value of the business. The company would then be sold at that price to a worker co-op made up of the founders and potentially other employees. However, it would not be a true liquidity event, as there would be no new cash coming into the company. Rather, the founders would be issued patient forms of preferred equity or revenue-share debt that would be retired at a pace determined by the co-op’s cash-flow so as not to undermine the company’s viability.

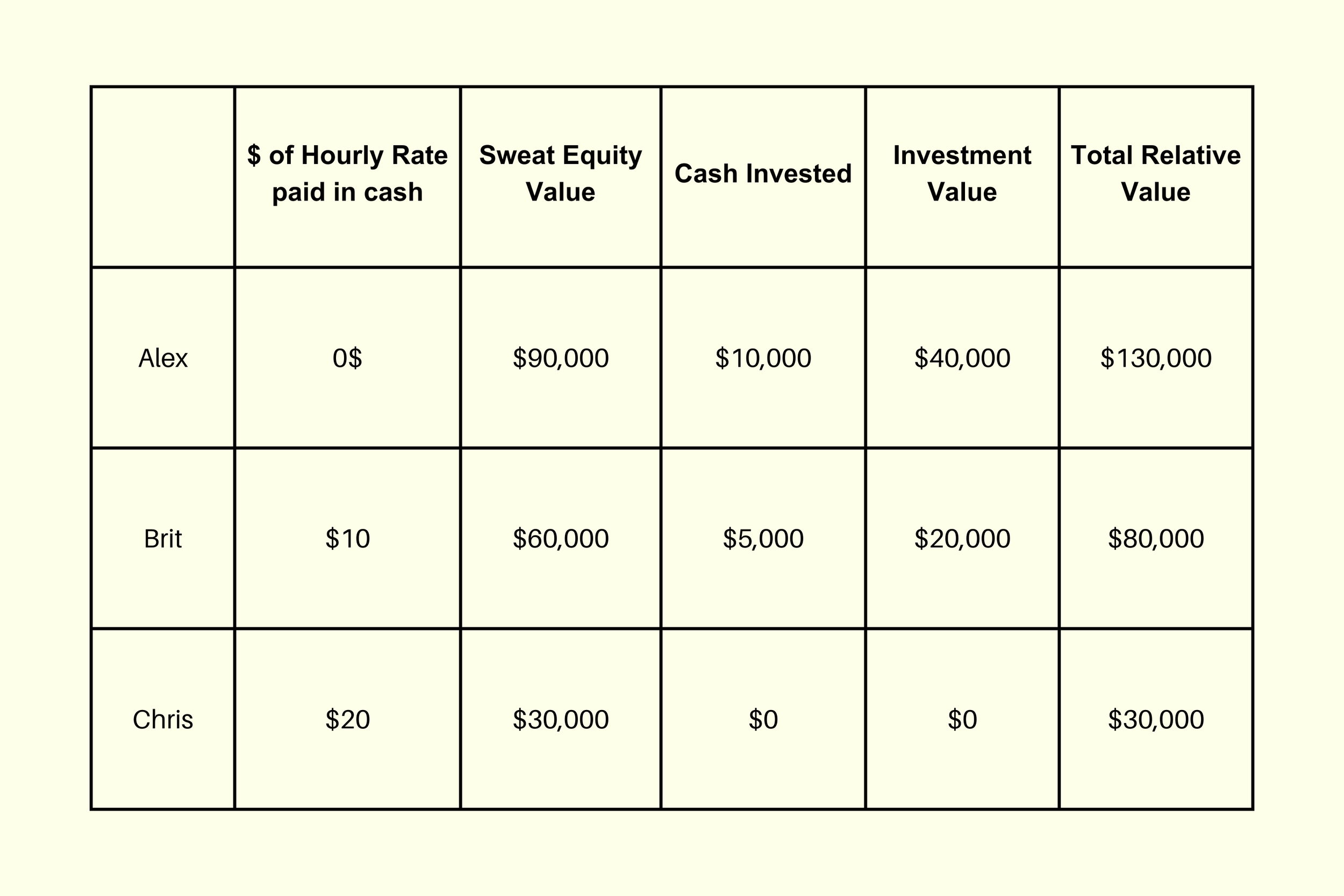

HYPOTHETICAL EXAMPLE: Alex, Brit, and Chris have decided that they want to launch a business that manufactures pie slicing knives. As they are all relatively equal in skills and experience, they agree to value their labor at $30/hour, and apply a 3x multiple to that value for any labor that is compensated with equity rather than cash. They also agree that they will value the cash investments used to launch the business at a 4x multiple. They each work 1,000 hours before “baking the pie” with the following results:

Slice Size

Upon “baking the pie” the founders begin to pay themselves fully for their labor in cash and freeze their relative ownership percentages of the company. They then obtain a 3rd party valuation, which suggests that the company is worth $200,000. This value is used as the basis for the conversion of the business to a co-op, with the founders both becoming co-op members on the buy side, and receiving a pro-rata portion of that value in non-voting preferred shares or a note paid over time on the sell side. Having fairly compensated the founders for their entrepreneurial labor, this process would result in a co-op with all members on equal footing in the new entity, including folks who joined the company post-founding and those who might join in the future.